MAKE YOUR VOICE HEARD ON THE DIGITAL SERVICES ACT (DSA)

On 15 December 2020, the European Commission presented its proposal for a new Digital Services Act (DSA). In the past years, online platforms have gained the power to impact our fundamental rights, our society and democracy. The DSA presents a chance to give people more rights and freedoms and start building a better internet, with clear rules for take-downs of illegal content, more transparency and choice for users.

Please help us improve the proposal by contributing comments and suggestions on the Commission proposal. Your contribution will be valuable for our work and amendments in the EU Parliament. The discussion will close on Sunday, 23 May at midnight. Our teams remain at your disposal for any questions or further comments at joseph.mcnamee@europarl.europa.eu.

You can also comment on the proposed Digital Markets Act, please click here.

Two ways to give feeback:

- You can leave a general remark concernig the text as whole here.

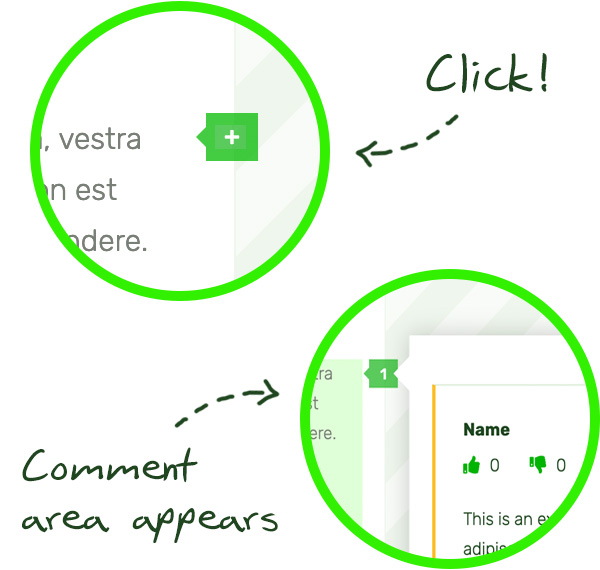

- You can amend single paragraphs using the plus icons. Furthermore, you can comment while reading (and don’t have to scroll to the very bottom). You can even discuss existing annotations.

Proposal for a

REGULATION OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL

on a Single Market For Digital Services (Digital Services Act) and amending Directive 2000/31/EC

THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN UNION,

Having regard to the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, and in particular Article 114 thereof,

Having regard to the proposal from the European Commission,

After transmission of the draft legislative act to the national parliaments,

Having regard to the opinion of the European Economic and Social Committee,

Having regard to the opinion of the Committee of the Regions,

Having regard to the opinion of the European Data Protection Supervisor,

Acting in accordance with the ordinary legislative procedure,

Whereas:

- Information society services and especially intermediary services have become an important part of the Union’s economy and daily life of Union citizens. Twenty years after the adoption of the existing legal framework applicable to such services laid down in Directive 2000/31/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council, new and innovative business models and services, such as online social networks and marketplaces, have allowed business users and consumers to impart and access information and engage in transactions in novel ways. A majority of Union citizens now uses those services on a daily basis. However, the digital transformation and increased use of those services has also resulted in new risks and challenges, both for individual users and for society as a whole.

- Member States are increasingly introducing, or are considering introducing, national laws on the matters covered by this Regulation, imposing, in particular, diligence requirements for providers of intermediary services. Those diverging national laws negatively affect the internal market, which, pursuant to Article 26 of the Treaty, comprises an area without internal frontiers in which the free movement of goods and services and freedom of establishment are ensured, taking into account the inherently cross-border nature of the internet, which is generally used to provide those services. The conditions for the provision of intermediary services across the internal market should be harmonised, so as to provide businesses with access to new markets and opportunities to exploit the benefits of the internal market, while allowing consumers and other recipients of the services to have increased choice.

- Responsible and diligent behaviour by providers of intermediary services is essential for a safe, predictable and trusted online environment and for allowing Union citizens and other persons to exercise their fundamental rights guaranteed in the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union (‘Charter’), in particular the freedom of expression and information and the freedom to conduct a business, and the right to non-discrimination.

- Therefore, in order to safeguard and improve the functioning of the internal market, a targeted set of uniform, effective and proportionate mandatory rules should be established at Union level. This Regulation provides the conditions for innovative digital services to emerge and to scale up in the internal market. The approximation of national regulatory measures at Union level concerning the requirements for providers of intermediary services is necessary in order to avoid and put an end to fragmentation of the internal market and to ensure legal certainty, thus reducing uncertainty for developers and fostering interoperability. By using requirements that are technology neutral, innovation should not be hampered but instead be stimulated.

- This Regulation should apply to providers of certain information society services as defined in Directive (EU) 2015/1535 of the European Parliament and of the Council, that is, any service normally provided for remuneration, at a distance, by electronic means and at the individual request of a recipient. Specifically, this Regulation should apply to providers of intermediary services, and in particular intermediary services consisting of services known as ‘mere conduit’, ‘caching’ and ‘hosting’ services, given that the exponential growth of the use made of those services, mainly for legitimate and socially beneficial purposes of all kinds, has also increased their role in the intermediation and spread of unlawful or otherwise harmful information and activities.

- In practice, certain providers of intermediary services intermediate in relation to services that may or may not be provided by electronic means, such as remote information technology services, transport, accommodation or delivery services. This Regulation should apply only to intermediary services and not affect requirements set out in Union or national law relating to products or services intermediated through intermediary services, including in situations where the intermediary service constitutes an integral part of another service which is not an intermediary service as specified in the case law of the Court of Justice of the European Union.

- In order to ensure the effectiveness of the rules laid down in this Regulation and a level playing field within the internal market, those rules should apply to providers of intermediary services irrespective of their place of establishment or residence, in so far as they provide services in the Union, as evidenced by a substantial connection to the Union.

- Such a substantial connection to the Union should be considered to exist where the service provider has an establishment in the Union or, in its absence, on the basis of the existence of a significant number of users in one or more Member States, or the targeting of activities towards one or more Member States. The targeting of activities towards one or more Member States can be determined on the basis of all relevant circumstances, including factors such as the use of a language or a currency generally used in that Member State, or the possibility of ordering products or services, or using a national top level domain. The targeting of activities towards a Member State could also be derived from the availability of an application in the relevant national application store, from the provision of local advertising or advertising in the language used in that Member State, or from the handling of customer relations such as by providing customer service in the language generally used in that Member State. A substantial connection should also be assumed where a service provider directs its activities to one or more Member State as set out in Article 17(1)(c) of Regulation (EU) 1215/2012 of the European Parliament and of the Council. On the other hand, mere technical accessibility of a website from the Union cannot, on that ground alone, be considered as establishing a substantial connection to the Union.

- This Regulation should complement, yet not affect the application of rules resulting from other acts of Union law regulating certain aspects of the provision of intermediary services, in particular Directive 2000/31/EC, with the exception of those changes introduced by this Regulation, Directive 2010/13/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council as amended, and Regulation (EU) …/.. of the European Parliament and of the Council – proposed Terrorist Content Online Regulation. Therefore, this Regulation leaves those other acts, which are to be considered lex specialis in relation to the generally applicable framework set out in this Regulation, unaffected. However, the rules of this Regulation apply in respect of issues that are not or not fully addressed by those other acts as well as issues on which those other acts leave Member States the possibility of adopting certain measures at national level.

- For reasons of clarity, it should also be specified that this Regulation is without prejudice to Regulation (EU) 2019/1148 of the European Parliament and of the Council and Regulation (EU) 2019/1150 of the European Parliament and of the Council, Directive 2002/58/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council and Regulation […/…] on temporary derogation from certain provisions of Directive 2002/58/EC as well as Union law on consumer protection, in particular Directive 2005/29/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council, Directive 2011/83/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council and Directive 93/13/EEC of the European Parliament and of the Council, as amended by Directive (EU) 2019/2161 of the European Parliament and of the Council37, and on the protection of personal data, in particular Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council. The protection of individuals with regard to the processing of personal data is solely governed by the rules of Union law on that subject, in particular Regulation (EU) 2016/679 and Directive 2002/58/EC. This Regulation is also without prejudice to the rules of Union law on working conditions.

- It should be clarified that this Regulation is without prejudice to the rules of Union law on copyright and related rights, which establish specific rules and procedures that should remain unaffected.

- In order to achieve the objective of ensuring a safe, predictable and trusted online environment, for the purpose of this Regulation the concept of “illegal content” should be defined broadly and also covers information relating to illegal content, products, services and activities. In particular, that concept should be understood to refer to information, irrespective of its form, that under the applicable law is either itself illegal, such as illegal hate speech or terrorist content and unlawful discriminatory content, or that relates to activities that are illegal, such as the sharing of images depicting child sexual abuse, unlawful non-consensual sharing of private images, online stalking, the sale of non-compliant or counterfeit products, the non-authorised use of copyright protected material or activities involving infringements of consumer protection law. In this regard, it is immaterial whether the illegality of the information or activity results from Union law or from national law that is consistent with Union law and what the precise nature or subject matter is of the law in question.

- Considering the particular characteristics of the services concerned and the corresponding need to make the providers thereof subject to certain specific obligations, it is necessary to distinguish, within the broader category of providers of hosting services as defined in this Regulation, the subcategory of online platforms. Online platforms, such as social networks or online marketplaces, should be defined as providers of hosting services that not only store information provided by the recipients of the service at their request, but that also disseminate that information to the public, again at their request. However, in order to avoid imposing overly broad obligations, providers of hosting services should not be considered as online platforms where the dissemination to the public is merely a minor and purely ancillary feature of another service and that feature cannot, for objective technical reasons, be used without that other, principal service, and the integration of that feature is not a means to circumvent the applicability of the rules of this Regulation applicable to online platforms. For example, the comments section in an online newspaper could constitute such a feature, where it is clear that it is ancillary to the main service represented by the publication of news under the editorial responsibility of the publisher.

- The concept of ‘dissemination to the public’, as used in this Regulation, should entail the making available of information to a potentially unlimited number of persons, that is, making the information easily accessible to users in general without further action by the recipient of the service providing the information being required, irrespective of whether those persons actually access the information in question. The mere possibility to create groups of users of a given service should not, in itself, be understood to mean that the information disseminated in that manner is not disseminated to the public. However, the concept should exclude dissemination of information within closed groups consisting of a finite number of pre-determined persons. Interpersonal communication services, as defined in Directive (EU) 2018/1972 of the European Parliament and of the Council, such as emails or private messaging services, fall outside the scope of this Regulation. Information should be considered disseminated to the public within the meaning of this Regulation only where that occurs upon the direct request by the recipient of the service that provided the information.

- Where some of the services provided by a provider are covered by this Regulation whilst others are not, or where the services provided by a provider are covered by different sections of this Regulation, the relevant provisions of this Regulation should apply only in respect of those services that fall within their scope.

- The legal certainty provided by the horizontal framework of conditional exemptions from liability for providers of intermediary services, laid down in Directive 2000/31/EC, has allowed many novel services to emerge and scale-up across the internal market. That framework should therefore be preserved. However, in view of the divergences when transposing and applying the relevant rules at national level, and for reasons of clarity and coherence, that framework should be incorporated in this Regulation. It is also necessary to clarify certain elements of that framework, having regard to case law of the Court of Justice of the European Union.

- The relevant rules of Chapter II should only establish when the provider of intermediary services concerned cannot be held liable in relation to illegal content provided by the recipients of the service. Those rules should not be understood to provide a positive basis for establishing when a provider can be held liable, which is for the applicable rules of Union or national law to determine. Furthermore, the exemptions from liability established in this Regulation should apply in respect of any type of liability as regards any type of illegal content, irrespective of the precise subject matter or nature of those laws.

- The exemptions from liability established in this Regulation should not apply where, instead of confining itself to providing the services neutrally, by a merely technical and automatic processing of the information provided by the recipient of the service, the provider of intermediary services plays an active role of such a kind as to give it knowledge of, or control over, that information. Those exemptions should accordingly not be available in respect of liability relating to information provided not by the recipient of the service but by the provider of intermediary service itself, including where the information has been developed under the editorial responsibility of that provider.

- In view of the different nature of the activities of ‘mere conduit’, ‘caching’ and ‘hosting’ and the different position and abilities of the providers of the services in question, it is necessary to distinguish the rules applicable to those activities, in so far as under this Regulation they are subject to different requirements and conditions and their scope differs, as interpreted by the Court of Justice of the European Union.

- A provider of intermediary services that deliberately collaborates with a recipient of the services in order to undertake illegal activities does not provide its service neutrally and should therefore not be able to benefit from the exemptions from liability provided for in this Regulation.

- A provider should be able to benefit from the exemptions from liability for ‘mere conduit’ and for ‘caching’ services when it is in no way involved with the information transmitted. This requires, among other things, that the provider does not modify the information that it transmits. However, this requirement should not be understood to cover manipulations of a technical nature which take place in the course of the transmission, as such manipulations do not alter the integrity of the information transmitted.

- In order to benefit from the exemption from liability for hosting services, the provider should, upon obtaining actual knowledge or awareness of illegal content, act expeditiously to remove or to disable access to that content. The removal or disabling of access should be undertaken in the observance of the principle of freedom of expression. The provider can obtain such actual knowledge or awareness through, in particular, its own-initiative investigations or notices submitted to it by individuals or entities in accordance with this Regulation in so far as those notices are sufficiently precise and adequately substantiated to allow a diligent economic operator to reasonably identify, assess and where appropriate act against the allegedly illegal content.

- In order to ensure the effective protection of consumers when engaging in intermediated commercial transactions online, certain providers of hosting services, namely, online platforms that allow consumers to conclude distance contracts with traders, should not be able to benefit from the exemption from liability for hosting service providers established in this Regulation, in so far as those online platforms present the relevant information relating to the transactions at issue in such a way that it leads consumers to believe that the information was provided by those online platforms themselves or by recipients of the service acting under their authority or control, and that those online platforms thus have knowledge of or control over the information, even if that may in reality not be the case. In that regard, is should be determined objectively, on the basis of all relevant circumstances, whether the presentation could lead to such a belief on the side of an average and reasonably well-informed consumer.

- The exemptions from liability established in this Regulation should not affect the possibility of injunctions of different kinds against providers of intermediary services, even where they meet the conditions set out as part of those exemptions. Such injunctions could, in particular, consist of orders by courts or administrative authorities requiring the termination or prevention of any infringement, including the removal of illegal content specified in such orders, issued in compliance with Union law, or the disabling of access to it.

- In order to create legal certainty and not to discourage activities aimed at detecting, identifying and acting against illegal content that providers of intermediary services may undertake on a voluntary basis, it should be clarified that the mere fact that providers undertake such activities does not lead to the unavailability of the exemptions from liability set out in this Regulation, provided those activities are carried out in good faith and in a diligent manner. In addition, it is appropriate to clarify that the mere fact that those providers take measures, in good faith, to comply with the requirements of Union law, including those set out in this Regulation as regards the implementation of their terms and conditions, should not lead to the unavailability of those exemptions from liability. Therefore, any such activities and measures that a given provider may have taken should not be taken into account when determining whether the provider can rely on an exemption from liability, in particular as regards whether the provider provides its service neutrally and can therefore fall within the scope of the relevant provision, without this rule however implying that the provider can necessarily rely thereon.

- Whilst the rules in Chapter II of this Regulation concentrate on the exemption from liability of providers of intermediary services, it is important to recall that, despite the generally important role played by those providers, the problem of illegal content and activities online should not be dealt with by solely focusing on their liability and responsibilities. Where possible, third parties affected by illegal content transmitted or stored online should attempt to resolve conflicts relating to such content without involving the providers of intermediary services in question. Recipients of the service should be held liable, where the applicable rules of Union and national law determining such liability so provide, for the illegal content that they provide and may disseminate through intermediary services. Where appropriate, other actors, such as group moderators in closed online environments, in particular in the case of large groups, should also help to avoid the spread of illegal content online, in accordance with the applicable law. Furthermore, where it is necessary to involve information society services providers, including providers of intermediary services, any requests or orders for such involvement should, as a general rule, be directed to the actor that has the technical and operational ability to act against specific items of illegal content, so as to prevent and minimise any possible negative effects for the availability and accessibility of information that is not illegal content.

- Since 2000, new technologies have emerged that improve the availability, efficiency, speed, reliability, capacity and security of systems for the transmission and storage of data online, leading to an increasingly complex online ecosystem. In this regard, it should be recalled that providers of services establishing and facilitating the underlying logical architecture and proper functioning of the internet, including technical auxiliary functions, can also benefit from the exemptions from liability set out in this Regulation, to the extent that their services qualify as ‘mere conduits’, ‘caching’ or hosting services. Such services include, as the case may be, wireless local area networks, domain name system (DNS) services, top–level domain name registries, certificate authorities that issue digital certificates, or content delivery networks, that enable or improve the functions of other providers of intermediary services. Likewise, services used for communications purposes, and the technical means of their delivery, have also evolved considerably, giving rise to online services such as Voice over IP, messaging services and web-based e-mail services, where the communication is delivered via an internet access service. Those services, too, can benefit from the exemptions from liability, to the extent that they qualify as ‘mere conduit’, ‘caching’ or hosting service.

- Providers of intermediary services should not be subject to a monitoring obligation with respect to obligations of a general nature. This does not concern monitoring obligations in a specific case and, in particular, does not affect orders by national authorities in accordance with national legislation, in accordance with the conditions established in this Regulation. Nothing in this Regulation should be construed as an imposition of a general monitoring obligation or active fact-finding obligation, or as a general obligation for providers to take proactive measures to relation to illegal content.

- Depending on the legal system of each Member State and the field of law at issue, national judicial or administrative authorities may order providers of intermediary services to act against certain specific items of illegal content or to provide certain specific items of information. The national laws on the basis of which such orders are issued differ considerably and the orders are increasingly addressed in cross-border situations. In order to ensure that those orders can be complied with in an effective and efficient manner, so that the public authorities concerned can carry out their tasks and the providers are not subject to any disproportionate burdens, without unduly affecting the rights and legitimate interests of any third parties, it is necessary to set certain conditions that those orders should meet and certain complementary requirements relating to the processing of those orders.

- Orders to act against illegal content or to provide information should be issued in compliance with Union law, in particular Regulation (EU) 2016/679 and the prohibition of general obligations to monitor information or to actively seek facts or circumstances indicating illegal activity laid down in this Regulation. The conditions and requirements laid down in this Regulation which apply to orders to act against illegal content are without prejudice to other Union acts providing for similar systems for acting against specific types of illegal content, such as Regulation (EU) …/…. [proposed Regulation addressing the dissemination of terrorist content online], or Regulation (EU) 2017/2394 that confers specific powers to order the provision of information on Member State consumer law enforcement authorities, whilst the conditions and requirements that apply to orders to provide information are without prejudice to other Union acts providing for similar relevant rules for specific sectors. Those conditions and requirements should be without prejudice to retention and preservation rules under applicable national law, in conformity with Union law and confidentiality requests by law enforcement authorities related to the non-disclosure of information.

- The territorial scope of such orders to act against illegal content should be clearly set out on the basis of the applicable Union or national law enabling the issuance of the order and should not exceed what is strictly necessary to achieve its objectives. In that regard, the national judicial or administrative authority issuing the order should balance the objective that the order seeks to achieve, in accordance with the legal basis enabling its issuance, with the rights and legitimate interests of all third parties that may be affected by the order, in particular their fundamental rights under the Charter. In addition, where the order referring to the specific information may have effects beyond the territory of the Member State of the authority concerned, the authority should assess whether the information at issue is likely to constitute illegal content in other Member States concerned and, where relevant, take account of the relevant rules of Union law or international law and the interests of international comity.

- The orders to provide information regulated by this Regulation concern the production of specific information about individual recipients of the intermediary service concerned who are identified in those orders for the purposes of determining compliance by the recipients of the services with applicable Union or national rules. Therefore, orders about information on a group of recipients of the service who are not specifically identified, including orders to provide aggregate information required for statistical purposes or evidence-based policy-making, should remain unaffected by the rules of this Regulation on the provision of information.

- Orders to act against illegal content and to provide information are subject to the rules safeguarding the competence of the Member State where the service provider addressed is established and laying down possible derogations from that competence in certain cases, set out in Article 3 of Directive 2000/31/EC, only if the conditions of that Article are met. Given that the orders in question relate to specific items of illegal content and information, respectively, where they are addressed to providers of intermediary services established in another Member State, they do not in principle restrict those providers’ freedom to provide their services across borders. Therefore, the rules set out in Article 3 of Directive 2000/31/EC, including those regarding the need to justify measures derogating from the competence of the Member State where the service provider is established on certain specified grounds and regarding the notification of such measures, do not apply in respect of those orders.

- In order to achieve the objectives of this Regulation, and in particular to improve the functioning of the internal market and ensure a safe and transparent online environment, it is necessary to establish a clear and balanced set of harmonised due diligence obligations for providers of intermediary services. Those obligations should aim in particular to guarantee different public policy objectives such as the safety and trust of the recipients of the service, including minors and vulnerable users, protect the relevant fundamental rights enshrined in the Charter, to ensure meaningful accountability of those providers and to empower recipients and other affected parties, whilst facilitating the necessary oversight by competent authorities.

- In that regard, it is important that the due diligence obligations are adapted to the type and nature of the intermediary service concerned. This Regulation therefore sets out basic obligations applicable to all providers of intermediary services, as well as additional obligations for providers of hosting services and, more specifically, online platforms and very large online platforms. To the extent that providers of intermediary services may fall within those different categories in view of the nature of their services and their size, they should comply with all of the corresponding obligations of this Regulation. Those harmonised due diligence obligations, which should be reasonable and non-arbitrary, are needed to achieve the identified public policy concerns, such as safeguarding the legitimate interests of the recipients of the service, addressing illegal practices and protecting fundamental rights online.

- In order to facilitate smooth and efficient communications relating to matters covered by this Regulation, providers of intermediary services should be required to establish a single point of contact and to publish relevant information relating to their point of contact, including the languages to be used in such communications. The point of contact can also be used by trusted flaggers and by professional entities which are under a specific relationship with the provider of intermediary services. In contrast to the legal representative, the point of contact should serve operational purposes and should not necessarily have to have a physical location .

- Providers of intermediary services that are established in a third country that offer services in the Union should designate a sufficiently mandated legal representative in the Union and provide information relating to their legal representatives, so as to allow for the effective oversight and, where necessary, enforcement of this Regulation in relation to those providers. It should be possible for the legal representative to also function as point of contact, provided the relevant requirements of this Regulation are complied with.

- Whilst the freedom of contract of providers of intermediary services should in principle be respected, it is appropriate to set certain rules on the content, application and enforcement of the terms and conditions of those providers in the interests of transparency, the protection of recipients of the service and the avoidance of unfair or arbitrary outcomes.

- To ensure an adequate level of transparency and accountability, providers of intermediary services should annually report, in accordance with the harmonised requirements contained in this Regulation, on the content moderation they engage in, including the measures taken as a result of the application and enforcement of their terms and conditions. However, so as to avoid disproportionate burdens, those transparency reporting obligations should not apply to providers that are micro- or small enterprises as defined in Commission Recommendation 2003/361/EC.

- Providers of hosting services play a particularly important role in tackling illegal content online, as they store information provided by and at the request of the recipients of the service and typically give other recipients access thereto, sometimes on a large scale. It is important that all providers of hosting services, regardless of their size, put in place user-friendly notice and action mechanisms that facilitate the notification of specific items of information that the notifying party considers to be illegal content to the provider of hosting services concerned (‘notice’), pursuant to which that provider can decide whether or not it agrees with that assessment and wishes to remove or disable access to that content (‘action’). Provided the requirements on notices are met, it should be possible for individuals or entities to notify multiple specific items of allegedly illegal content through a single notice. The obligation to put in place notice and action mechanisms should apply, for instance, to file storage and sharing services, web hosting services, advertising servers and paste bins, in as far as they qualify as providers of hosting services covered by this Regulation.

- The rules on such notice and action mechanisms should be harmonised at Union level, so as to provide for the timely, diligent and objective processing of notices on the basis of rules that are uniform, transparent and clear and that provide for robust safeguards to protect the right and legitimate interests of all affected parties, in particular their fundamental rights guaranteed by the Charter, irrespective of the Member State in which those parties are established or reside and of the field of law at issue. The fundamental rights include, as the case may be, the right to freedom of expression and information, the right to respect for private and family life, the right to protection of personal data, the right to non-discrimination and the right to an effective remedy of the recipients of the service; the freedom to conduct a business, including the freedom of contract, of service providers; as well as the right to human dignity, the rights of the child, the right to protection of property, including intellectual property, and the right to non-discrimination of parties affected by illegal content.

- Where a hosting service provider decides to remove or disable information provided by a recipient of the service, for instance following receipt of a notice or acting on its own initiative, including through the use of automated means, that provider should inform the recipient of its decision, the reasons for its decision and the available redress possibilities to contest the decision, in view of the negative consequences that such decisions may have for the recipient, including as regards the exercise of its fundamental right to freedom of expression. That obligation should apply irrespective of the reasons for the decision, in particular whether the action has been taken because the information notified is considered to be illegal content or incompatible with the applicable terms and conditions. Available recourses to challenge the decision of the hosting service provider should always include judicial redress.

- To avoid disproportionate burdens, the additional obligations imposed on online platforms under this Regulation should not apply to micro or small enterprises as defined in Recommendation 2003/361/EC of the Commission, unless their reach and impact is such that they meet the criteria to qualify as very large online platforms under this Regulation. The consolidation rules laid down in that Recommendation help ensure that any circumvention of those additional obligations is prevented. The exemption of micro- and small enterprises from those additional obligations should not be understood as affecting their ability to set up, on a voluntary basis, a system that complies with one or more of those obligations.

- Recipients of the service should be able to easily and effectively contest certain decisions of online platforms that negatively affect them. Therefore, online platforms should be required to provide for internal complaint-handling systems, which meet certain conditions aimed at ensuring that the systems are easily accessible and lead to swift and fair outcomes. In addition, provision should be made for the possibility of out-of-court dispute settlement of disputes, including those that could not be resolved in satisfactory manner through the internal complaint-handling systems, by certified bodies that have the requisite independence, means and expertise to carry out their activities in a fair, swift and cost-effective manner. The possibilities to contest decisions of online platforms thus created should complement, yet leave unaffected in all respects, the possibility to seek judicial redress in accordance with the laws of the Member State concerned.

- For contractual consumer-to-business disputes over the purchase of goods or services, Directive 2013/11/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council ensures that Union consumers and businesses in the Union have access to quality-certified alternative dispute resolution entities. In this regard, it should be clarified that the rules of this Regulation on out-of-court dispute settlement are without prejudice to that Directive, including the right of consumers under that Directive to withdraw from the procedure at any stage if they are dissatisfied with the performance or the operation of the procedure.

- Action against illegal content can be taken more quickly and reliably where online platforms take the necessary measures to ensure that notices submitted by trusted flaggers through the notice and action mechanisms required by this Regulation are treated with priority, without prejudice to the requirement to process and decide upon all notices submitted under those mechanisms in a timely, diligent and objective manner. Such trusted flagger status should only be awarded to entities, and not individuals, that have demonstrated, among other things, that they have particular expertise and competence in tackling illegal content, that they represent collective interests and that they work in a diligent and objective manner. Such entities can be public in nature, such as, for terrorist content, internet referral units of national law enforcement authorities or of the European Union Agency for Law Enforcement Cooperation (‘Europol’) or they can be non-governmental organisations and semi-public bodies, such as the organisations part of the INHOPE network of hotlines for reporting child sexual abuse material and organisations committed to notifying illegal racist and xenophobic expressions online. For intellectual property rights, organisations of industry and of right-holders could be awarded trusted flagger status, where they have demonstrated that they meet the applicable conditions. The rules of this Regulation on trusted flaggers should not be understood to prevent online platforms from giving similar treatment to notices submitted by entities or individuals that have not been awarded trusted flagger status under this Regulation, from otherwise cooperating with other entities, in accordance with the applicable law, including this Regulation and Regulation (EU) 2016/794 of the European Parliament and of the Council.

- The misuse of services of online platforms by frequently providing manifestly illegal content or by frequently submitting manifestly unfounded notices or complaints under the mechanisms and systems, respectively, established under this Regulation undermines trust and harms the rights and legitimate interests of the parties concerned. Therefore, there is a need to put in place appropriate and proportionate safeguards against such misuse. Information should be considered to be manifestly illegal content and notices or complaints should be considered manifestly unfounded where it is evident to a layperson, without any substantive analysis, that the content is illegal respectively that the notices or complaints are unfounded. Under certain conditions, online platforms should temporarily suspend their relevant activities in respect of the person engaged in abusive behaviour. This is without prejudice to the freedom by online platforms to determine their terms and conditions and establish stricter measures in the case of manifestly illegal content related to serious crimes. For reasons of transparency, this possibility should be set out, clearly and in sufficiently detail, in the terms and conditions of the online platforms. Redress should always be open to the decisions taken in this regard by online platforms and they should be subject to oversight by the competent Digital Services Coordinator. The rules of this Regulation on misuse should not prevent online platforms from taking other measures to address the provision of illegal content by recipients of their service or other misuse of their services, in accordance with the applicable Union and national law. Those rules are without prejudice to any possibility to hold the persons engaged in misuse liable, including for damages, provided for in Union or national law.

- An online platform may in some instances become aware, such as through a notice by a notifying party or through its own voluntary measures, of information relating to certain activity of a recipient of the service, such as the provision of certain types of illegal content, that reasonably justify, having regard to all relevant circumstances of which the online platform is aware, the suspicion that the recipient may have committed, may be committing or is likely to commit a serious criminal offence involving a threat to the life or safety of person, such as offences specified in Directive 2011/93/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council. In such instances, the online platform should inform without delay the competent law enforcement authorities of such suspicion, providing all relevant information available to it, including where relevant the content in question and an explanation of its suspicion. This Regulation does not provide the legal basis for profiling of recipients of the services with a view to the possible identification of criminal offences by online platforms. Online platforms should also respect other applicable rules of Union or national law for the protection of the rights and freedoms of individuals when informing law enforcement authorities.

- In order to contribute to a safe, trustworthy and transparent online environment for consumers, as well as for other interested parties such as competing traders and holders of intellectual property rights, and to deter traders from selling products or services in violation of the applicable rules, online platforms allowing consumers to conclude distance contracts with traders should ensure that such traders are traceable. The trader should therefore be required to provide certain essential information to the online platform, including for purposes of promoting messages on or offering products. That requirement should also be applicable to traders that promote messages on products or services on behalf of brands, based on underlying agreements. Those online platforms should store all information in a secure manner for a reasonable period of time that does not exceed what is necessary, so that it can be accessed, in accordance with the applicable law, including on the protection of personal data, by public authorities and private parties with a legitimate interest, including through the orders to provide information referred to in this Regulation.

- To ensure an efficient and adequate application of that obligation, without imposing any disproportionate burdens, the online platforms covered should make reasonable efforts to verify the reliability of the information provided by the traders concerned, in particular by using freely available official online databases and online interfaces, such as national trade registers and the VAT Information Exchange System, or by requesting the traders concerned to provide trustworthy supporting documents, such as copies of identity documents, certified bank statements, company certificates and trade register certificates. They may also use other sources, available for use at a distance, which offer a similar degree of reliability for the purpose of complying with this obligation. However, the online platforms covered should not be required to engage in excessive or costly online fact-finding exercises or to carry out verifications on the spot. Nor should such online platforms, which have made the reasonable efforts required by this Regulation, be understood as guaranteeing the reliability of the information towards consumer or other interested parties. Such online platforms should also design and organise their online interface in a way that enables traders to comply with their obligations under Union law, in particular the requirements set out in Articles 6 and 8 of Directive 2011/83/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council, Article 7 of Directive 2005/29/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council47 and Article 3 of Directive 98/6/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council48.

- In view of the particular responsibilities and obligations of online platforms, they should be made subject to transparency reporting obligations, which apply in addition to the transparency reporting obligations applicable to all providers of intermediary services under this Regulation. For the purposes of determining whether online platforms may be very large online platforms that are subject to certain additional obligations under this Regulation, the transparency reporting obligations for online platforms should include certain obligations relating to the publication and communication of information on the average monthly active recipients of the service in the Union.

- Online advertisement plays an important role in the online environment, including in relation to the provision of the services of online platforms. However, online advertisement can contribute to significant risks, ranging from advertisement that is itself illegal content, to contributing to financial incentives for the publication or amplification of illegal or otherwise harmful content and activities online, or the discriminatory display of advertising with an impact on the equal treatment and opportunities of citizens. In addition to the requirements resulting from Article 6 of Directive 2000/31/EC, online platforms should therefore be required to ensure that the recipients of the service have certain individualised information necessary for them to understand when and on whose behalf the advertisement is displayed. In addition, recipients of the service should have information on the main parameters used for determining that specific advertising is to be displayed to them, providing meaningful explanations of the logic used to that end, including when this is based on profiling. The requirements of this Regulation on the provision of information relating to advertisement is without prejudice to the application of the relevant provisions of Regulation (EU) 2016/679, in particular those regarding the right to object, automated individual decision-making, including profiling and specifically the need to obtain consent of the data subject prior to the processing of personal data for targeted advertising. Similarly, it is without prejudice to the provisions laid down in Directive 2002/58/EC in particular those regarding the storage of information in terminal equipment and the access to information stored therein.

- Given the importance of very large online platforms, due to their reach, in particular as expressed in number of recipients of the service, in facilitating public debate, economic transactions and the dissemination of information, opinions and ideas and in influencing how recipients obtain and communicate information online, it is necessary to impose specific obligations on those platforms, in addition to the obligations applicable to all online platforms. Those additional obligations on very large online platforms are necessary to address those public policy concerns, there being no alternative and less restrictive measures that would effectively achieve the same result.

- Very large online platforms may cause societal risks, different in scope and impact from those caused by smaller platforms. Once the number of recipients of a platform reaches a significant share of the Union population, the systemic risks the platform poses have a disproportionately negative impact in the Union. Such significant reach should be considered to exist where the number of recipients exceeds an operational threshold set at 45 million, that is, a number equivalent to 10% of the Union population. The operational threshold should be kept up to date through amendments enacted by delegated acts, where necessary. Such very large online platforms should therefore bear the highest standard of due diligence obligations, proportionate to their societal impact and means.

- In view of the network effects characterising the platform economy, the user base of an online platform may quickly expand and reach the dimension of a very large online platform, with the related impact on the internal market. This may be the case in the event of exponential growth experienced in short periods of time, or by a large global presence and turnover allowing the online platform to fully exploit network effects and economies of scale and of scope. A high annual turnover or market capitalisation can in particular be an indication of fast scalability in terms of user reach. In those cases, the Digital Services Coordinator should be able to request more frequent reporting from the platform on the user base to be able to timely identify the moment at which that platform should be designated as a very large online platform for the purposes of this Regulation.

- Very large online platforms are used in a way that strongly influences safety online, the shaping of public opinion and discourse, as well as on online trade. The way they design their services is generally optimised to benefit their often advertising-driven business models and can cause societal concerns. In the absence of effective regulation and enforcement, they can set the rules of the game, without effectively identifying and mitigating the risks and the societal and economic harm they can cause. Under this Regulation, very large online platforms should therefore assess the systemic risks stemming from the functioning and use of their service, as well as by potential misuses by the recipients of the service, and take appropriate mitigating measures.

- Three categories of systemic risks should be assessed in-depth. A first category concerns the risks associated with the misuse of their service through the dissemination of illegal content, such as the dissemination of child sexual abuse material or illegal hate speech, and the conduct of illegal activities, such as the sale of products or services prohibited by Union or national law, including counterfeit products. For example, and without prejudice to the personal responsibility of the recipient of the service of very large online platforms for possible illegality of his or her activity under the applicable law, such dissemination or activities may constitute a significant systematic risk where access to such content may be amplified through accounts with a particularly wide reach. A second category concerns the impact of the service on the exercise of fundamental rights, as protected by the Charter of Fundamental Rights, including the freedom of expression and information, the right to private life, the right to non-discrimination and the rights of the child. Such risks may arise, for example, in relation to the design of the algorithmic systems used by the very large online platform or the misuse of their service through the submission of abusive notices or other methods for silencing speech or hampering competition. A third category of risks concerns the intentional and, oftentimes, coordinated manipulation of the platform’s service, with a foreseeable impact on health, civic discourse, electoral processes, public security and protection of minors, having regard to the need to safeguard public order, protect privacy and fight fraudulent and deceptive commercial practices. Such risks may arise, for example, through the creation of fake accounts, the use of bots, and other automated or partially automated behaviours, which may lead to the rapid and widespread dissemination of information that is illegal content or incompatible with an online platform’s terms and conditions.

- Very large online platforms should deploy the necessary means to diligently mitigate the systemic risks identified in the risk assessment. Very large online platforms should under such mitigating measures consider, for example, enhancing or otherwise adapting the design and functioning of their content moderation, algorithmic recommender systems and online interfaces, so that they discourage and limit the dissemination of illegal content, adapting their decision-making processes, or adapting their terms and conditions. They may also include corrective measures, such as discontinuing advertising revenue for specific content, or other actions, such as improving the visibility of authoritative information sources. Very large online platforms may reinforce their internal processes or supervision of any of their activities, in particular as regards the detection of systemic risks. They may also initiate or increase cooperation with trusted flaggers, organise training sessions and exchanges with trusted flagger organisations, and cooperate with other service providers, including by initiating or joining existing codes of conduct or other self-regulatory measures. Any measures adopted should respect the due diligence requirements of this Regulation and be effective and appropriate for mitigating the specific risks identified, in the interest of safeguarding public order, protecting privacy and fighting fraudulent and deceptive commercial practices, and should be proportionate in light of the very large online platform’s economic capacity and the need to avoid unnecessary restrictions on the use of their service, taking due account of potential negative effects on the fundamental rights of the recipients of the service.

- Very large online platforms should, where appropriate, conduct their risk assessments and design their risk mitigation measures with the involvement of representatives of the recipients of the service, representatives of groups potentially impacted by their services, independent experts and civil society organisations.

- Given the need to ensure verification by independent experts, very large online platforms should be accountable, through independent auditing, for their compliance with the obligations laid down by this Regulation and, where relevant, any complementary commitments undertaking pursuant to codes of conduct and crises protocols. They should give the auditor access to all relevant data necessary to perform the audit properly. Auditors should also be able to make use of other sources of objective information, including studies by vetted researchers. Auditors should guarantee the confidentiality, security and integrity of the information, such as trade secrets, that they obtain when performing their tasks and have the necessary expertise in the area of risk management and technical competence to audit algorithms. Auditors should be independent, so as to be able to perform their tasks in an adequate and trustworthy manner. If their independence is not beyond doubt, they should resign or abstain from the audit engagement.

- The audit report should be substantiated, so as to give a meaningful account of the activities undertaken and the conclusions reached. It should help inform, and where appropriate suggest improvements to the measures taken by the very large online platform to comply with their obligations under this Regulation. The report should be transmitted to the Digital Services Coordinator of establishment and the Board without delay, together with the risk assessment and the mitigation measures, as well as the platform’s plans for addressing the audit’s recommendations. The report should include an audit opinion based on the conclusions drawn from the audit evidence obtained. A positive opinion should be given where all evidence shows that the very large online platform complies with the obligations laid down by this Regulation or, where applicable, any commitments it has undertaken pursuant to a code of conduct or crisis protocol, in particular by identifying, evaluating and mitigating the systemic risks posed by its system and services. A positive opinion should be accompanied by comments where the auditor wishes to include remarks that do not have a substantial effect on the outcome of the audit. A negative opinion should be given where the auditor considers that the very large online platform does not comply with this Regulation or the commitments undertaken.

- A core part of a very large online platform’s business is the manner in which information is prioritised and presented on its online interface to facilitate and optimise access to information for the recipients of the service. This is done, for example, by algorithmically suggesting, ranking and prioritising information, distinguishing through text or other visual representations, or otherwise curating information provided by recipients. Such recommender systems can have a significant impact on the ability of recipients to retrieve and interact with information online. They also play an important role in the amplification of certain messages, the viral dissemination of information and the stimulation of online behaviour. Consequently, very large online platforms should ensure that recipients are appropriately informed, and can influence the information presented to them. They should clearly present the main parameters for such recommender systems in an easily comprehensible manner to ensure that the recipients understand how information is prioritised for them. They should also ensure that the recipients enjoy alternative options for the main parameters, including options that are not based on profiling of the recipient.

- Advertising systems used by very large online platforms pose particular risks and require further public and regulatory supervision on account of their scale and ability to target and reach recipients of the service based on their behaviour within and outside that platform’s online interface. Very large online platforms should ensure public access to repositories of advertisements displayed on their online interfaces to facilitate supervision and research into emerging risks brought about by the distribution of advertising online, for example in relation to illegal advertisements or manipulative techniques and disinformation with a real and foreseeable negative impact on public health, public security, civil discourse, political participation and equality. Repositories should include the content of advertisements and related data on the advertiser and the delivery of the advertisement, in particular where targeted advertising is concerned.

- In order to appropriately supervise the compliance of very large online platforms with the obligations laid down by this Regulation, the Digital Services Coordinator of establishment or the Commission may require access to or reporting of specific data. Such a requirement may include, for example, the data necessary to assess the risks and possible harms brought about by the platform’s systems, data on the accuracy, functioning and testing of algorithmic systems for content moderation, recommender systems or advertising systems, or data on processes and outputs of content moderation or of internal complaint-handling systems within the meaning of this Regulation. Investigations by researchers on the evolution and severity of online systemic risks are particularly important for bridging information asymmetries and establishing a resilient system of risk mitigation, informing online platforms, Digital Services Coordinators, other competent authorities, the Commission and the public. This Regulation therefore provides a framework for compelling access to data from very large online platforms to vetted researchers. All requirements for access to data under that framework should be proportionate and appropriately protect the rights and legitimate interests, including trade secrets and other confidential information, of the platform and any other parties concerned, including the recipients of the service.

- Given the complexity of the functioning of the systems deployed and the systemic risks they present to society, very large online platforms should appoint compliance officers, which should have the necessary qualifications to operationalise measures and monitor the compliance with this Regulation within the platform’s organisation. Very large online platforms should ensure that the compliance officer is involved, properly and in a timely manner, in all issues which relate to this Regulation. In view of the additional risks relating to their activities and their additional obligations under this Regulation, the other transparency requirements set out in this Regulation should be complemented by additional transparency requirements applicable specifically to very large online platforms, notably to report on the risk assessments performed and subsequent measures adopted as provided by this Regulation.

- To facilitate the effective and consistent application of the obligations in this Regulation that may require implementation through technological means, it is important to promote voluntary industry standards covering certain technical procedures, where the industry can help develop standardised means to comply with this Regulation, such as allowing the submission of notices, including through application programming interfaces, or about the interoperability of advertisement repositories. Such standards could in particular be useful for relatively small providers of intermediary services. The standards could distinguish between different types of illegal content or different types of intermediary services, as appropriate.

- The Commission and the Board should encourage the drawing-up of codes of conduct to contribute to the application of this Regulation. While the implementation of codes of conduct should be measurable and subject to public oversight, this should not impair the voluntary nature of such codes and the freedom of interested parties to decide whether to participate. In certain circumstances, it is important that very large online platforms cooperate in the drawing-up and adhere to specific codes of conduct. Nothing in this Regulation prevents other service providers from adhering to the same standards of due diligence, adopting best practices and benefitting from the guidance provided by the Commission and the Board, by participating in the same codes of conduct.

- It is appropriate that this Regulation identify certain areas of consideration for such codes of conduct. In particular, risk mitigation measures concerning specific types of illegal content should be explored via self- and co-regulatory agreements. Another area for consideration is the possible negative impacts of systemic risks on society and democracy, such as disinformation or manipulative and abusive activities. This includes coordinated operations aimed at amplifying information, including disinformation, such as the use of bots or fake accounts for the creation of fake or misleading information, sometimes with a purpose of obtaining economic gain, which are particularly harmful for vulnerable recipients of the service, such as children. In relation to such areas, adherence to and compliance with a given code of conduct by a very large online platform may be considered as an appropriate risk mitigating measure. The refusal without proper explanations by an online platform of the Commission’s invitation to participate in the application of such a code of conduct could be taken into account, where relevant, when determining whether the online platform has infringed the obligations laid down by this Regulation.

- The rules on codes of conduct under this Regulation could serve as a basis for already established self-regulatory efforts at Union level, including the Product Safety Pledge, the Memorandum of Understanding against counterfeit goods, the Code of Conduct against illegal hate speech as well as the Code of practice on disinformation. In particular for the latter, the Commission will issue guidance for strengthening the Code of practice on disinformation as announced in the European Democracy Action Plan.

- The provision of online advertising generally involves several actors, including intermediary services that connect publishers of advertising with advertisers. Codes of conducts should support and complement the transparency obligations relating to advertisement for online platforms and very large online platforms set out in this Regulation in order to provide for flexible and effective mechanisms to facilitate and enhance the compliance with those obligations, notably as concerns the modalities of the transmission of the relevant information. The involvement of a wide range of stakeholders should ensure that those codes of conduct are widely supported, technically sound, effective and offer the highest levels of user-friendliness to ensure that the transparency obligations achieve their objectives.

- In case of extraordinary circumstances affecting public security or public health, the Commission may initiate the drawing up of crisis protocols to coordinate a rapid, collective and cross-border response in the online environment. Extraordinary circumstances may entail any unforeseeable event, such as earthquakes, hurricanes, pandemics and other serious cross-border threats to public health, war and acts of terrorism, where, for example, online platforms may be misused for the rapid spread of illegal content or disinformation or where the need arises for rapid dissemination of reliable information. In light of the important role of very large online platforms in disseminating information in our societies and across borders, such platforms should be encouraged in drawing up and applying specific crisis protocols. Such crisis protocols should be activated only for a limited period of time and the measures adopted should also be limited to what is strictly necessary to address the extraordinary circumstance. Those measures should be consistent with this Regulation, and should not amount to a general obligation for the participating very large online platforms to monitor the information which they transmit or store, nor actively to seek facts or circumstances indicating illegal content.

- The task of ensuring adequate oversight and enforcement of the obligations laid down in this Regulation should in principle be attributed to the Member States. To this end, they should appoint at least one authority with the task to apply and enforce this Regulation. Member States should however be able to entrust more than one competent authority, with specific supervisory or enforcement tasks and competences concerning the application of this Regulation, for example for specific sectors, such as electronic communications’ regulators, media regulators or consumer protection authorities, reflecting their domestic constitutional, organisational and administrative structure.

- Given the cross-border nature of the services at stake and the horizontal range of obligations introduced by this Regulation, the authority appointed with the task of supervising the application and, where necessary, enforcing this Regulation should be identified as a Digital Services Coordinator in each Member State. Where more than one competent authority is appointed to apply and enforce this Regulation, only one authority in that Member State should be identified as a Digital Services Coordinator. The Digital Services Coordinator should act as the single contact point with regard to all matters related to the application of this Regulation for the Commission, the Board, the Digital Services Coordinators of other Member States, as well as for other competent authorities of the Member State in question. In particular, where several competent authorities are entrusted with tasks under this Regulation in a given Member State, the Digital Services Coordinator should coordinate and cooperate with those authorities in accordance with the national law setting their respective tasks, and should ensure effective involvement of all relevant authorities in the supervision and enforcement at Union level.

- The Digital Services Coordinator, as well as other competent authorities designated under this Regulation, play a crucial role in ensuring the effectiveness of the rights and obligations laid down in this Regulation and the achievement of its objectives. Accordingly, it is necessary to ensure that those authorities act in complete independence from private and public bodies, without the obligation or possibility to seek or receive instructions, including from the government, and without prejudice to the specific duties to cooperate with other competent authorities, the Digital Services Coordinators, the Board and the Commission. On the other hand, the independence of these authorities should not mean that they cannot be subject, in accordance with national constitutions and without endangering the achievement of the objectives of this Regulation, to national control or monitoring mechanisms regarding their financial expenditure or to judicial review, or that they should not have the possibility to consult other national authorities, including law enforcement authorities or crisis management authorities, where appropriate.

- Member States can designate an existing national authority with the function of the Digital Services Coordinator, or with specific tasks to apply and enforce this Regulation, provided that any such appointed authority complies with the requirements laid down in this Regulation, such as in relation to its independence. Moreover, Member States are in principle not precluded from merging functions within an existing authority, in accordance with Union law. The measures to that effect may include, inter alia, the preclusion to dismiss the President or a board member of a collegiate body of an existing authority before the expiry of their terms of office, on the sole ground that an institutional reform has taken place involving the merger of different functions within one authority, in the absence of any rules guaranteeing that such dismissals do not jeopardise the independence and impartiality of such members.

- In the absence of a general requirement for providers of intermediary services to ensure a physical presence within the territory of one of the Member States, there is a need to ensure clarity under which Member State’s jurisdiction those providers fall for the purposes of enforcing the rules laid down in Chapters III and IV by the national competent authorities. A provider should be under the jurisdiction of the Member State where its main establishment is located, that is, where the provider has its head office or registered office within which the principal financial functions and operational control are exercised. In respect of providers that do not have an establishment in the Union but that offer services in the Union and therefore fall within the scope of this Regulation, the Member State where those providers appointed their legal representative should have jurisdiction, considering the function of legal representatives under this Regulation. In the interest of the effective application of this Regulation, all Member States should, however, have jurisdiction in respect of providers that failed to designate a legal representative, provided that the principle of ne bis in idem is respected. To that aim, each Member State that exercises jurisdiction in respect of such providers should, without undue delay, inform all other Member States of the measures they have taken in the exercise of that jurisdiction.

- Member States should provide the Digital Services Coordinator, and any other competent authority designated under this Regulation, with sufficient powers and means to ensure effective investigation and enforcement. Digital Services Coordinators should in particular be able to search for and obtain information which is located in its territory, including in the context of joint investigations, with due regard to the fact that oversight and enforcement measures concerning a provider under the jurisdiction of another Member State should be adopted by the Digital Services Coordinator of that other Member State, where relevant in accordance with the procedures relating to cross-border cooperation.

- Member States should set out in their national law, in accordance with Union law and in particular this Regulation and the Charter, the detailed conditions and limits for the exercise of the investigatory and enforcement powers of their Digital Services Coordinators, and other competent authorities where relevant, under this Regulation.

- In the course of the exercise of those powers, the competent authorities should comply with the applicable national rules regarding procedures and matters such as the need for a prior judicial authorisation to enter certain premises and legal professional privilege. Those provisions should in particular ensure respect for the fundamental rights to an effective remedy and to a fair trial, including the rights of defence, and, the right to respect for private life. In this regard, the guarantees provided for in relation to the proceedings of the Commission pursuant to this Regulation could serve as an appropriate point of reference. A prior, fair and impartial procedure should be guaranteed before taking any final decision, including the right to be heard of the persons concerned, and the right to have access to the file, while respecting confidentiality and professional and business secrecy, as well as the obligation to give meaningful reasons for the decisions. This should not preclude the taking of measures, however, in duly substantiated cases of urgency and subject to appropriate conditions and procedural arrangements. The exercise of powers should also be proportionate to, inter alia the nature and the overall actual or potential harm caused by the infringement or suspected infringement. The competent authorities should in principle take all relevant facts and circumstances of the case into account, including information gathered by competent authorities in other Member States.

- Member States should ensure that violations of the obligations laid down in this Regulation can be sanctioned in a manner that is effective, proportionate and dissuasive, taking into account the nature, gravity, recurrence and duration of the violation, in view of the public interest pursued, the scope and kind of activities carried out, as well as the economic capacity of the infringer. In particular, penalties should take into account whether the provider of intermediary services concerned systematically or recurrently fails to comply with its obligations stemming from this Regulation, as well as, where relevant, whether the provider is active in several Member States.

- In order to ensure effective enforcement of this Regulation, individuals or representative organisations should be able to lodge any complaint related to compliance with this Regulation with the Digital Services Coordinator in the territory where they received the service, without prejudice to this Regulation’s rules on jurisdiction. Complaints should provide a faithful overview of concerns related to a particular intermediary service provider’s compliance and could also inform the Digital Services Coordinator of any more cross-cutting issues. The Digital Services Coordinator should involve other national competent authorities as well as the Digital Services Coordinator of another Member State, and in particular the one of the Member State where the provider of intermediary services concerned is established, if the issue requires cross-border cooperation.

- Member States should ensure that Digital Services Coordinators can take measures that are effective in addressing and proportionate to certain particularly serious and persistent infringements. Especially where those measures can affect the rights and interests of third parties, as may be the case in particular where the access to online interfaces is restricted, it is appropriate to require that the measures be ordered by a competent judicial authority at the Digital Service Coordinators’ request and are subject to additional safeguards. In particular, third parties potentially affected should be afforded the opportunity to be heard and such orders should only be issued when powers to take such measures as provided by other acts of Union law or by national law, for instance to protect collective interests of consumers, to ensure the prompt removal of web pages containing or disseminating child pornography, or to disable access to services are being used by a third party to infringe an intellectual property right, are not reasonably available.