The indigenous Sámi people living in the Arctic have a saying: “Eennâm Lii Eellim”. Land is life. These communities rely on the land and the wildlife living there for their survival and the preservation of their culture. But climate change is threatening the fragile balance of people and nature in the Arctic region.

Our trainee in the Greens/EFA Group, Julia Kerkelä, was born and raised above the Arctic Circle, and explores what is happening to the Sámi as different industries eye up traditional Sámi land.

Recently, the largest source of rare minerals in Europe was found in the northern area of Kiruna, Sweden. Rare minerals are used to produce high-tech goods, like batteries for electric cars, electronic devices, and wind turbines. It might sound like good news for Europe, but the discovery has wreaked havoc on the indigenous community, the Sámi.

For the Sámi, reindeer are vital to their way of life. They provide for food, clothing, snow shoes, tools and even simple things like buttons. Reindeer are inextricably linked to the continued survival – and cultural heritage – of the Sámi, going back countless generations. We learned that the Sámi arrived in northern Scandinavia at the end of the last ice age. As the existing mine near Kiruna keeps expanding, reindeer herders in the area have to quit their traditions and livelihoods.

Unique wildlife is under attack in the Arctic

The Kiruna mine expansion is not only dangerous for the Sámi. The impact on the unique Arctic flora and fauna has been fatal. Arctic wildlife and landscapes are unique and irreplaceable. Global warming and industrial development are a serious risk for the sensitive biodiversity. This is because they render habitats uninhabitable for the wildlife that depend on them. Many species are unable to move further north due to global warming and melting ice caps. They’re staring extinction in the face. Once you get to the northernmost tip of the world, there’s literally nowhere else to go.

In the fight for land in the Arctic, local communities seem to lose time after time. Mining, forestry and energy production play a significantly bigger role than the thriving Arctic culture when it comes to political decision-making at all levels. The EU should be a force for protecting the Arctic as a global heritage. But the Sámi in Kiruna say that the way the European Commission is approaching the green transition is threatening their way of life and their very existence. An EU strategy that was built to protect life on the earth should not seek success with the price of social and cultural harm.

No climate justice without social justice – also in the Arctic

Don’t get me wrong – renewable energies are the solution to the climate crisis. But what we really need is a change of mindset. Everlasting growth in a renewable world will still put pressure on ecosystems and untouched lands as we continue to guzzle more energy and resources. No matter if it is oil, gas or rare ressources. Climate justice includes social justice, and especially the integrity of indigenous communities and their lands. Any violation towards this is not acceptable.

But what is at stake in the Arctic? How do the Sámi live in precarious balance with the changing wildlife and climate? And how can we support the local communities in the Arctic who are preserving the biodiversity and scenery of the area, and by extension their culture?

A fragile balance – how is climate change threatening the Arctic?

In the Arctic, climate change and the loss of biodiversity are more interlinked than anywhere else on Earth. Temperatures in the Arctic are rising four times as fast as the global average. We are already witnessing the changes – with melting sea ice, warming permafrost and the Arctic treeline accelerating towards the pole. What is happening in the Arctic is likely to provoke extreme temperature events in other areas of the world. The effects will be global – and not only environmental, but financial, cultural, and social.

The Arctic is home to more than four million people. Approximately 10 percent of them are indigenous. The indigenous people of the Arctic hold significant cultural, social, and historical differences. But a common feature for most is the fact that they have already undergone substantial changes to their way of life. This is due to national policies, industrialisation and social change.

Globally, the lands inhabited by indigenous peoples contain 80% of the world’s remaining biodiversity. Besides undergoing changes, what connects the indigenous peoples all around the world is their connection to the land that they live on.

Climate change is threatening the life of the Sámi people

In Northern Europe, the Sámi people inhabit the region of Sápmi. Sápmi covers large parts of northern Norway, Sweden, Finland, and the Murmansk Oblast in Russia. Traditional Sámi livelihoods are reindeer herding, fishing, hunting, gathering and handicrafts. Climate change is threatening the continuity of these livelihoods and culture.I

One example of this is how global warming has changed the weather conditions in the Arctic. Warmer global temperatures have meant that there is now more rain falling in the Arctic than snow. Rain creates a layer of ice on top of the snow when it freezes. This prevents animals like reindeer from getting to their food. This has devastating consequences on wildlife, but also on cultural practices, like reindeer herding.

Another example is that of ice roads, a typical form of transportation in the Arctic. The warming weather has caused changes in the river and lake ice. This is making it very dangerous – or impossible – to use ice roads as a way of transportation. Climate change is deeply affecting people in many communities. But in the case of the Arctic it’s threatening the cultural survival of the indigenous population.

What is “Crusty Snow”? The eight seasons of the Arctic

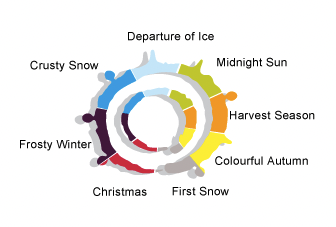

The Arctic year has never been divided into four seasons. Instead, the people living in the Arctic have structured time into eight periods.

From “First Snow” to “Crusty Snow”, to “Harvest Season” and “Colourful Autumn”. Arctic seasons are almost like rhythms that help the people adapt to the rhythms of the river, the forest, and the landscape. They aren’t defined by the Earth’s rotation, but by the changing of culture during the time of year.

Spring brings with it crusted snow, meaning it is safe to get on your skis without falling into the snow while wandering through the forests and the fells. When the ice in the rivers breaks up in the late spring, and starts its journey downriver, it means the first plants will soon begin to bloom and the reindeers will give birth to calves. The landscape suddenly fills with life, new and returning.

Based on the rhythms of the year, the locals know what to prepare for. When it is safe to walk on the river ice. When it is the right time to move reindeers from winter to summer pastures. Fishing and hunting – every task has its season. This is especially true for the indigenous Sámi community of northern Europe. They define their years by the behaviour of the reindeer. Reindeer are extremely sensitive to variations in weather and temperatures.

Land is life – how do the indigenous Sámi live in balance with nature?

The Sámi in the Arctic have a saying: “Eennâm Lii Eellim”. Land is life.

By adjusting their daily lives with the changing of seasons, the Sámi balance their livelihoods in nature. They avoid scarcity of food and other resources they need to survive. A long history of living on the land has made it possible for the Sámi people to use their traditional ecological knowledge to protect and restore their environment’s biodiversity.

The northern way of life and the northern state of mind are a mentality which imitates nature. Nature is in a constant state of change – moving from one season to another – and so are the people. Always preparing for tomorrow. While this being one of the most defining parts of not only the Sámi culture, but the arctic culture overall, the eight seasons still define the thinking and acting of the people in the area through all generations. But because of the effects of climate change, and the increasing pressure for exploitation of the mineral deposits and the land use of the region, the Sámi are unsure about the changes happening in the landscape.

The river, that would always tell us what tomorrow would look like, can’t do that anymore after being strangled by hydropower plants. The warming climate has brought longer summers and warmer winters, merging the eight seasons into four with mid-seasons disappearing. It is becoming harder and harder to prepare for tomorrow, without the signs that we were used to seeing by observing nature.

The green transition must also be fair: can climate adaptation turn into a cultural threat?

Arctic regions are witnessing some of the most rapid rises in temperature. Climate adaptation (taking actions to reduce the harm caused by climate change, like switching to renewable energy) is a priority. But to do this in a fair way, we must be mindful of the existing discrimination against indigenous communities.

It’s the wealthy western civilisation that has caused the climate crisis. But the people who are the least responsible are paying the highest price. Indigenous peoples are among the first to face the direct consequences of climate change. This is due to their dependence and close relationship to the environment. On top of that, climate change exacerbates the difficulties already faced by indigenous peoples. This includes the exploitation of their land and resources, human rights violations, and political marginalisation.

We need to stop exploiting the Arctic now

Growing pressure in the Arctic and conflict over land is pitting different interest groups against each other. In the case of the Sámi people, both sovereign states and multi-billion-dollar companies are now interested in the same land the Sámi have herded for centuries.

Historically, the Global North has achieved a high standard of living by exploiting the labour and land of the Global South. But this can also take place within a country or an area. In the case of the Arctic, land that was previously frozen solid is becoming more and more accessible for industry due to the melting of permafrost and the Arctic Ocean.

We also need to be careful of ‘green colonialism’. As we invest in renewable energy and infrastructure, it can often happen at the expense of marginalized communities, like indigenous communities. Take, for example, the giant wind farms built in northern Norway which have destroyed reindeer pastures and migration routes.

Getting justice for the Sámi – how can the EU help?

If we want to make sure that EU laws protect Sámi rights and culture, the Sámi must be involved in making those laws.

In the last couple of years, the Sámi Council, a voluntary Sámi organisation that promotes Sámi rights and interests, created the Sapmi project. Established with EU funding, the aim was to raise awareness about the Sámi people within the European institutions. Sámi civil society became involved in EU decision-making processes. Luckily the Sámi people´s concerns were heard on crucial new EU policies, such as the Farm to Fork agricultural strategy, the Biodiversity strategy, the Just Transition Fund, and the European Climate Pact.

Meanwhile, in the European Parliament, our Greens/EFA MEP, Alice Bah Kuhnke, who is from Sweden, has called for “real political leadership”. She calls for a climate transition that must not come at the expense of climate justice.

’’We cannot save our planet and humanity by continuing to exploit the earth and sacrificing indigenous peoples rights. We need real political leadership in this time of climate crisis, to make sure that the climate transition goes hand in hand with climate justice – for all, including indigenous populations.”

Alice Bah Kuhnke, Greens/EFA MEP, Sweden

We still have a lot of questions to answer, and a lot more to learn about our Arctic indigenous peoples. As the pressure on the Arctic grows, the question at the centre of it all is: who has the right to the land? And how can we find solutions for a more inclusive and sustainable future? One thing is for sure, the traditional Sámi world view can teach us all much more than we ever thought.