Meccanismo “Notice and Action”

Il gruppo Verdi/ALE sta elaborando una nuova legislazione dell’UE per un meccanismo di “Notice & Action”. Il progetto di testo legislativo mira a fornire una base per la futura legislazione dell’UE. È aperto alla consultazione del pubblico fino al 1° novembre.

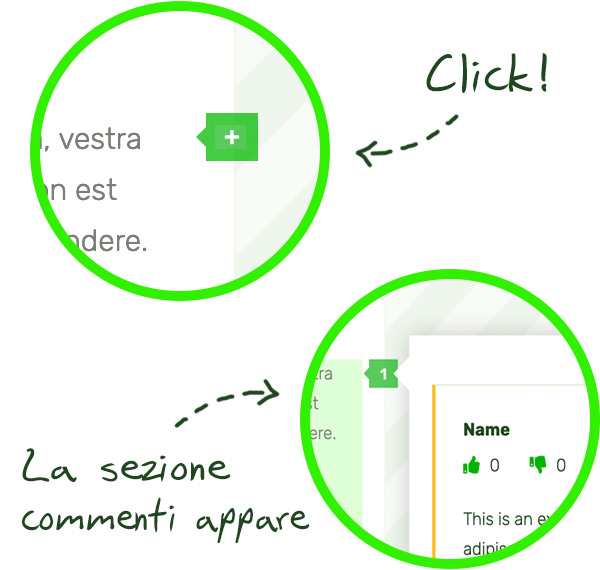

Per dare il vostro contributo sulle regole modello, utilizzate la sezione commenti. È anche possibile paragrafi specifici o i commenti di altri.

Al momento non esistono regole chiare per le piattaforme online, come YouTube, Twitter, Facebook o Instagram, e come dovrebbero affrontare i reclami degli utenti e i contenuti potenzialmente illegali online.

Nell’ultimo anno, il Parlamento europeo ha chiesto una legislazione per regolamentare le piattaforme online. La Commissione europea ha continuato a rinviare tale legislazione negli ultimi 7 anni, mentre pochissimi Stati membri hanno effettivamente introdotto leggi nazionali.

Di conseguenza, le piattaforme online hanno iniziato a creare le proprie regole, basate su standard comunitari, che hanno portato molte volte alla diffusione di contenuti di hate speech e altri contenuti problematici, ma anche a un’eccessiva rimozione dei contenuti leciti online.

Due modi per contribuire:

Potete lasciare qui un’osservazione generale che riguarda il testo nel suo insieme.

- È possibile modificare singoli paragrafi utilizzando le icone + . Inoltre, è possibile commentare durante la lettura (e non è necessario scorrere fino in fondo). Potete anche commentare le annotazioni già esistenti.

Regulation on procedures for notifying and acting on illegal content hosted by information society services

(“Regulation on Notice and Action procedures”)

Chapter I

General Provisions

Article 1

Subject matter and objective

- This Regulation lays down rules to establish procedures for notifying and acting on illegal content hosted by information society services to and ensure their proper functioning.

This Regulation seeks to contribute to the proper functioning of the internal market by ensuring the free movement of intermediary information society services in full respect of the Charter on Fundamental Rights, in particular its Article 11 on the freedom of expression and information.

Article 2

Definitions

For the purpose of the Regulation:

- ‘hosting service provider’ means any information society service provider that hosts, stores, selects, references publicly available content or distributes content publicly provided by a user of the service.

- ‘content’ means any concept, expression or information in any format such as text, images, audio and video.

- ‘illegal content’ refers to ‘illegal information’ found illegal under the law of the Member State where it is hosted.

- ‘content moderation’ means the practice of sorting content provided by a recipient of a service by applying a pre-determined set of rules and guidelines in order to ensure that the content complies with legal and regulatory requirements, and terms and conditions, as well as any resulting measure taken by the hosting service provider, such as removal of the content or the deletion or suspension of the user’s account.

- ‘content provider’ refers to any recipient of a hosting service.

- ‘notice’: means any communication about illegal content addressed to a hosting service provider with the objective of obtaining the removal of or the disabling of access to that content.

- ‘notice provider’: means any natural or legal person submitting a notice.

- ‘counter notice’: means a notice through which the content provider challenges a claim of illegality as regards content provided by the said provider.

‘terms and conditions’ means all terms, conditions or rules, irrespective of their name or form, which govern the contractual relationship between the content hosting platform and its users and which are unilaterally determined by the hosting service provider.

Chapter II

Notifying Illegal Content

Article 3

The right to notify

The hosting service provider shall establish an easily accessible and user-friendly mechanism that allows natural or legal persons to notify the concerned illegal content hosted by that provider. Such mechanism shall allow for notification by electronic means.

Article 4

Standards for notices

- Hosting service providers shall ensure that notice providers can submit notices which are sufficiently precise and adequately substantiated to enable the hosting service provider to take an informed decision about the follow-up to that notice. For that purpose, notices shall at least contain the following elements:

- an explanation of the reason on which the content can be considered illegal.

- proof or any other documentation to support the claim and potential legal grounds.

- a clear indication of the exact location of the illegal content (URL and timestamp where appropriate).

- a declaration of good faith that the information provided is accurate.

- Notice providers shall be given the choice whether to include their contact details in the notice. Where they decide to do so, their anonymity towards the content provider shall be ensured; the identification of notice providers should however be provided in cases of violations of personality rights or of intellectual property rights.

- Notices shall not automatically trigger legal liability nor should they impose any removal requirement for specific pieces of the content or for the legality assessment.

Chapter III

Acting on Illegal Content

Article 5

The right of a notice provider to be informed

- Upon receipt of a notice, the hosting service provider shall immediately send a confirmation of receipt to the notice provider.

- Upon the decision to act or not on the basis of a notice, the hosting service provider informs the notice provider accordingly.

Article 6

The right of a content provider to be informed

- Upon receipt of a notice, the hosting service provider shall immediately inform the content provider about the notice, the decision taken and the reasoning behind hosting service providerit, how such decision was made, if the decision was made by a human only or aided by an automated content moderation tools, about the possibility to issue a counter-notice and how to appeal a decision by either party with the hosting service provider, courts or other entities.

- The first paragraph of this article shall only apply if the content provider has supplied sufficient contact details to the hosting service provider.

The first paragraph shall not apply if justified reasons of public policy and public security as provided for by law and in particular where this would run counter to the prevention and prosecution of serious criminal offences. In this case the information should be provided as soon as the reasons not to inform cease to exist or an investigation has concluded.

Article 7

Complaint and redress mechanism

- Hosting service providers shall establish effective and accessible mechanisms allowing content providers whose content has been removed or access to it disabled by manual or automated means to submit a counter-notice against the action of the hosting service provider requesting reinstatement of their content.

- Hosting service providers shall promptly examine every complaint that they receive and reinstate the content without undue delay where the removal or disabling of access was unjustified. They shall inform the complainant about the outcome of the examination.

- The hosting service provider shall ensure that, upon receipt of a notice, the provider of that content shall have the right to contest any action by issuing a counter-notice.

The hosting service provider shall promptly assess the counter-notice and take due account of it.

- If the counter-notice has provided reasonable grounds to consider that the content is not illegal, hosting service providers may decide not to act or to restore, without undue delay, access to the content that was removed or to which access was temporarily disabled, and inform the content provider of such restoration.The hosting service provider shall ensure that the provider of the counter-notice and the provider of the initial notice are informed about the follow-up to a counter-notice, granted their contact details were provided.

- Paragraphs 1 to 3 of this article are without prejudice to the right to an effective remedy and to a fair trial enshrined in Article 47 of the Charter.

Chapter IV

Transparency on Notice and Action Procedures

Article 8

The right of transparency on notice-and-action procedures

- Hosting service providers shall provide clear information about their notice and action procedures in their terms and conditions.

- Hosting service providers shall publish annual reports in a standardized format including:

- the number of all notices received under the notice-and-action system categorised by the type of content.

- information about the number and type of illegal content which has been removed or access to it disabled, including the corresponding timeframes per type of content.

- the number of erroneous takedowns.

- The type of entities that issued the notices (private individuals, organisations, corporations, trusted flaggers, Member State and EU bodies, etc.) and the total number of their notices.

- information about the number of complaint procedures, contested decisions and actions taken by the hosting service providers;

- the description of the content moderation model applied by the hosting service provider, including the existence, process, rationale, reasoning and possible outcome of any automated systems used.

- information about the number of redress procedures initiated and decisions taken by the competent authority in accordance with national law.

- the measures they adopt with regards to repeated infringers to ensure that the measures are effective in tackling such systemic abusive behaviour.

- When automatic content moderation tools are used, transparency and accountability shall be ensured by independent and impartial public oversight. To that end, national supervisory authorities shall have access to the software documentation, the facilities, and the datasets, hardware and software used.

Article 9

Transparency obligations for Member States

Member States shall publish annual reports including:

- the number of all judicial procedures issued to hosting service providers categorised by type of content.

- information on the number of cases of successful detection, investigation and prosecution of offences that were notified to hosting service providers by notice providers and Member State authorities.

Chapter V

Independent Dispute Settlement

Article 10

Independent dispute settlement

- Member States shall establish independent dispute settlement bodies for the purpose of providing quick and efficient extra-judicial recourse to appeal decisions on content moderation.

- The independent dispute settlement bodies shall meet the following requirements:

- they are composed of legal experts while taking into account the principle of gender balance;

- they are impartial and independent;

- their services are affordable for users of the hosting services concerned;

- they are capable of providing their services in the language of the terms and conditions which govern the contractual relationship between the provider of hosting services and the user concerned;

- they are easily accessible either physically in the place of establishment or residence of the business user, or remotely using communication technologies;

- they are capable of providing their mediation services without undue delay.

- The referral of a question regarding content moderation to an independent dispute settlement body shall be without prejudice to the right to an effective remedy and to a fair trial enshrined in Article 47 of the Charter.

Article 11

Procedural rules for independent dispute settlement

- The content provider, the notice provider and non-profit entities with a legitimate interest in defending freedom of expression and information shall have the right to refer a question of content moderation to the competent independent dispute settlement body in case of a dispute regarding a content moderation decision taken by the hosting service provider.

- As regards jurisdiction, the competent independent dispute settlement body shall be that located in the Member State in which the notice has been filed. For natural persons, it should always be possible to bring complaints to the independent dispute settlement body of the Member States of residence.

I commenti sono chiusi.

79 commenti

Commenti generali

Commenti all'articolo

-

-

-

-

-

-

borked sentence:

“…and the reasoning behind hosting service PROVIDERIT, how such decision was made, if..”

Also, that sentence is far too long.

Furthermore, the sentence currently includes “upon receipt of a notice, the hosting service provider shall immediately inform the content provider about [..] the decision taken”, implying decisions have to be immediately after receipt of notice, or otherwise granting wriggle room for notifying not immediately, but only after (some time has passed and) a decision was reached. This should be cleared up.Reference -

-

“entities that issued the notices” are “notice providers”, as defined. Use the latter.

How is the hosting service provider to know the type of notice providers? Are they to do identity verification on them? Does this implicitly disallow anonymous notices?

At the very least needs “insofar far as known” added, but preferably should be removed altogether.Reference -

-

-

“Member State in which the notice has been filed” is not defined.

If a resident of A, while being in B, electronically submits a notice to content hosting provider incorporated in C, whose facilities in D receive and handle the notice, where has the notice been filed?“complaints” is not defined.

“As regards jurisdiction, …” followed by a rule about non-jurisdictional alternate courts. Seriously, just drop Articles 10+11.Reference

-

Formal requirements for valid notice are an essential part of the legislative framework. The information that defines the valid notice sets the whole mechanism in motion. This is currently missing in the draft. “Any communication about illegal content” is simply any notice that is submitted by private or public parties.Reference

-

-

Is this meant to be cumulative or not? If it is cumulative, then I’m not sure what the additional criteria (selects, stores, references) bring. If not, I’m not sure that referencing publicly available content is tantamount to hosting it (although it can be). Hosts don’t generally distribute (broadcast) content. What is wrong with the description in ECD 14.1 that needs to be fixed?Reference

-

-

-

-

Alternative suggestion:

The process of assessing the[il]legality or potential unacceptability of third-party content, in order to decide whether certain content posted, or attempted to be posted, online should be demoted (i.e. left online but rendered less accessible), demonitised, left online or removed, for some or all audiences, by the service on which it was posted.Reference -

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

I must admit that I am not quite sure why content moderation is included in the scope of this proposal. Platforms should not encouraged to active look for illegal content and content moderation is more linked to the content that violates their terms of service => which should not be in the scope of the law at first place.Reference

-

-

-

What do you mean by “follow up to that notice”? It seems that you leave the final decision and balancing of rights exercise in hands of hosting providers which especially in the context of illegal content is something we are not able to support. Private companies cannot be in charge of a matter that should be taken care of by public authorities. Member States cannot escape legal responsibility by delegating a function or a service to a private actor. By introducing a broad obligation upon private actors to apply proactive measures to assess and potentially remove content and at the same time making them fully responsible for potential interference with fundamental rights raises issues of compatibility with the positive obligations of the state under the EU Charter.Reference

-

Nowhere in the text is specified who can submit valid notice to hosting service providers. And this is directly linked to the requirement of actual knowledge, which is also omitted by the text. In order to safeguard the principle of legal certainty, you need to clarify what constitutes actual knowledge about illegal content being hosted by online platforms. The legal framework should provide for minimum standards when this type of knowledge is obtained by platforms. The court order issued by an independent judicial body should always constitute actual knowledge. Platforms’ failure to comply with the court order should result in the loss of liability exemption.Reference

-

Why is terms of service relevant for illegal content? Notice and action procedures established by the legislative framework should only tackle illegal content, given that the assessment of content’s legality is done by judicial independent authority (at least in the ideal world). I would keep ToS and content moderation outside the scope of this proposal.Reference

-

Alternative list of formal requirements for valid notice:

A clearly formulated reason for a complaint accompanied with the legal basis for the assessment of the content;

Exact location of the content that can be determined by the URL link;

Evidence that substantiates the claim submitted by a notifier;Identity of a notifier only if it is necessary for further investigation of the claim and in full compliance with existing legal standards. In general, notifiers should not be forced to disclose their identity when reporting content.Reference

-

I’m interested to know how this proposal would interact with measures that companies are supposed to take to counter harmful content, since this definition would cover harmful content as well, and in general notice and action mechanisms – based on companies Terms of Services – would also apply to such content. The IMCO report suggests that “measures to combat harmful content should be regularly evaluated and developed further”. Now, how is this evaluation going to happen if the really good transparency measures that are outlined in article 9 don’t apply to these measures?

Do you envisage to have similar safeguards in the ex ante part of the DSA, where new obligations would apply for dominant/gatekeeper or systemic platforms?Reference -

-

Specified time frames and defined procedures should be specified by N/A measures such as: the time to forward the notification to the content provider; the time for the content provider to respond with a counter-notification; the time to make a decision about removing content or maintaining it online;

the time to inform the involved parties about the decision taken; and

the time to initiate a review of the decision by the courts.Moreover, we advocate for counter-notices submitted prior to any action taken by platforms against the notified content.Reference

-

-

I thought it was ambiguous on this point, but perhaps given the definition of “notice” it should be read to mean only notices of allegedly illegal content. So at minimum it should be clarified, and then personally I would clarify it to include TOS violations, as Joe discusses. I would also include some proportionality wiggle room for smaller platforms.Reference

-

And the number of removal requests delivered by governments using some mechanism other than a judicial procedure! IRUs should be captured here, as should be other back-room government communications. At least aspirationally…

To be honest I think getting transparency from specific agencies, regulators, or competent authorities (as in TERREG) that regularly do work touching platform content moderation would be less work, and more value, than trying to gather this info from judicial systems. But perhaps I underestimate how efficient the existing tracking of judicial rulings is.Reference -

This is extremely sweeping. I would want to understand the details much more. z. B, which data sets is this talking about? Does it mean platforms save copies of every piece of removed (or challenged but not removed) content for potential future audits? If so, and if the GDPR issues can be resolved, that’s fascinating and let’s build other transparency possibilities on top of it! If not, what exactly are these authorities reviewing, and is the benefit worth the cost to all concerned? Etc.Reference

-

-

Notice providers should be furnished with a receipt from the posting service provider that is referenced by an unique identifier code, authenticated by an electronic certificate. This receipt must include the full content of the elements of the the notice, the contact details -if they have been provided- of the notice provider, the time and the date when the notice was sent.Reference

-

-

-

-

-

-

Consider replacing with “Upon the decision to act or not on the basis of a notice, the hosting service provider informs notice provider about the decision taken and the reasoning behind the decision, how such decision was made, if the decision was made by a human only or aided by an automated content moderation tools, and how to appeal a decision by either party with the hosting service provider, courts or other entities”.Reference

-

-

We have generally understood content moderation as the way in which platforms address requests for takedowns and other measures (e.g. labelling) under their Terms of Service. If a company has to comply with legal requirements, we tend to think of it as online content regulation/ compliance with legal requirements.Reference

-

In the ECD, hosting is a function. In practice it’s been applied to a range of services, including search, though search has also been found to fall under the ‘mere conduit’ exemption. Defining new categories besides those already existing in the ECD is likely to be fraught with difficulties. Before doing so, we would recommend considering what a new definition would add to the existing ones and what the implications are for liability. Also worth considering: the extent to which the ECD should be amended to codify the case-law of the CJEU on this point.Reference

-

“any communication” sounds very broad: presumably a ‘valid’ notice would have to fulfil certain requirements? As noted by Access Now above, those requirements should be an essential part of any notice and action framework.

Also, at this point, the notice can only be about “allegedly” illegal content, unless the notice comes from a court.

“removal or disabling of access”: this assumes that these are the only options available. If legal but harmful content is included (which we do not recommend), labelling or other measures might be a better solutionReference

-

We agree with Access Now’s comments above. We have set out the types of requirements that should be applicable in a notice-and-notice system here: https://www.article19.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/ARTICLE-19s-Recommendations-for-the-EU-Digital-Services-Act-FINAL.pdf

Identification of the notice provider may not be justified if personality rights include e.g. harassment claims. Identification is more likely to be justified in relation to defamation and intellectual property rights claims.Reference

-

One of the key problems with Article 14 of the E-Commerce Directive is that there’s been a lot of legal uncertainty about what kind of notice is sufficient for providers to obtain “actual knowledge” of illegality and therefore trigger the loss of *immunity* from liability. In ARTICLE 19’s view, actual knowledge of *illegality* can only be obtained by a court order.

In practice, the lack of clarity on what constitutes sufficient notice has led a lot of providers to simply remove content upon notice since they do not want to take the risk of being found liable if the case goes to court. Under the ECD, providers do not automatically lose immunity from liability when they receive notice from a third party and do nothing. But doing nothing increases the risk that they might lose it and be found liable if the notifier decides to go to court.

Going back to this proposal, creating a clearer complaints mechanism is a positive step forward. That (valid?) notices do not automatically trigger the loss of immunity is also positive.

At the same time, this sytem does not really provide a lot of legal certainty for providers and is ultimately more likely to result in a notice-and-takedown system, which is problematic for freedom of expression.Reference

-

Under Article 6 (1) of this proposal, the company makes a decision about legality and does so without hearing first from the content provider. This is problematic for two reasons:

First, as we’ve mentioned before, we don’t think that private companies should decide whether content is legal or not. Even if this is just meant as an assessment of the company’s own liability risk, small companies are unlikely to have teams of lawyers who are able to make this assessment, they are more likely to remove content upon receipt of notice.

Secondly, the decision is made without the content provider having been given an opportunity to contest the allegation made against him or her. It is therefore inconsistent with due process standards.

We agree with Access’s comment above that counter-notice should at least take place before a decision is made.Reference

-

In this proposal, a counter-notice does not seem too different from a notice of appeal. As noted above, we believe that counter-notices should at least take place before a decision is made, though our strong preference is for counter-notices to be used as a means for the content provider and the notifier to resolve the dispute between themselves rather than the intermediary making a decision (Cf: https://www.article19.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/ARTICLE-19s-Recommendations-for-the-EU-Digital-Services-Act-FINAL.pdf)Reference

-

I know this is opening up Pandora’s box a little bit, but there should ideally be some frame for the decisions hosting providers take.

1. If a hosting provider doesn’t act, they lose their liability protections. So ther eis an incentive to act.

2. If a hosting provider doesn’t remove allegedly infringing content, they will likely be sued by the rightsholders. So there is an incentive to remove content.

3. If the hosting provider removes legal content, users are much less likely to sue. So there is a much weaker incentive to not overblock.Not a ready baked solution, but some thoughts:

One way to overcome this is to have organisations that regularly send fraudulent notices be banned from the N&A system for a period of time. But that is on the platform side. Platforms themselves could risk losing their liability protections if they systemically overblock.Reference -

Suggest discussing the concept of information society services. The ECD explains that it relates to services normally provided for remuneration, a relatively broad concept. On the one hand, a broad understanding (as supported by legal doctrine) benefits an entire range of service providers, which fall under the freedom of establishment and limited liability provisions. On the other hand, it could be to the disadvantage of those providers, who do not necessarily seek profit or receive benefits other than monetary remuneration.Reference

-

-

It’s very important to make clear that intermediaries should not be held liable for choosing not to remove content simply because they received a private notification by a user (as you do under para 3). In this sense, it may be reasonable to amend the phrase “take an informed decision about the follow-up to that notice” and replace it with “to inform the hosting service provider about potentially illegal content and behavior”. The alternative is to link it to the notion of “to act or not” in Art 5(2), but this would entail a significant risk to burden online intermediaries with legal assessments. It consequently leads to problems related to liability for non-acting (as the assessment can lead to positive knowledge about the (non)illegality of user hosted content).Reference

-

Beware of the pitfalls of good faith clauses for individual users. What is the consequence of not acting in good faith? And good faith about what exactly? Individual users can hardly assess legal concepts and the nature of infringements. We suggest reformulating this phrase to avoid the negative consequences of existing mis-guided co-regulatory approaches. For example, the NetzDG has compelled certain platforms to threaten users with the disabling of their accounts in case that notifications turn out to be legally inaccurate.Reference

-

We suggest using the concept of “terms that are not individually negotiated”. If you introduce a chapter on terms and conditions/terms of service, we suggest to reflect on problems related to transparency and presentation. (https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2020/08/our-eu-policy-principles-user-controls)Reference

-

We support that notices should not automatically trigger legal liability (nor should they impose any removal requirements). However, you cannot escape the problem of liability for user content without addressing the situations under which liability is actually triggered. In order to protect freedom of expression and access to justice, we recommend to work with the general principle that actual knowledge of illegality is only obtained by intermediaries if they are presented with a court order.Reference

-

-

It is very important to ensure algorithmic transparency for users where platforms use automated tools for content moderation (https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2020/08/our-eu-policy-principles-user-controls). We also suggest adding a reference to related privacy rights, such as the right not to be subjected to automated individual decision-making under Art 22 GDPR.Reference

-

+1 to noyb’s comment. if you wish to regulate local competences, you will need to use the termini of domicile/habitual residence (or other connecting factors). also, the last sentence is not in line with the BXL Ia Regulation (speaking about domicile rather than residence) and leads to different competent bodies depending on whether the individual acts or whether a non-profit body acts on behalf of that individual (being a non-natural person). Notably, the ADR directive does not regulate these aspects (which gives more options to the affected individual to act thanks to potential multiple competent bodies).Reference

The whole thing is rather pointless as-is.

It establishes a notice-and-takedown procedure, as well as the possibility to file counter notices and appeal to an alternate court system. But it doesn’t (as written now) change the current legal situation that hosting service providers are liable for the content they’re hosting on behalf of content providers, and therefore will aggressively purge content that might be illegal.

In fact, even if a content provider files a counter notice, and the “independent dispute settlement body” decides that the content should be reinstated, the hosting service provider WILL STILL BE LIABLE in case an actual court decides that the content in question was, indeed, illegal! Luckily, the hosting service provider is free to ignore any decision by that “independent dispute settlement body”, and therefore can and will simply keep the content offline to avoid that liability. IOW: the status quo.

What would be needed is:

1) the counter notice including an explicit affirmation that the content provider considers the content legal and is prepared to face legal responsibility for publicizing the content.

2) the option for the hosting service provider to verify the identity of the content provider in a matter suitable to get them into an actual court.

3) an explicit indemnification of the hosting service provider for hosting the content, provided 1) and 2) have occurred.

…and none of that “independent dispute settlement” stuff. There’s noting to settle, because the problem is not a dispute between the content provider and the hosting service provider. The problem is determining the legality of the content. And that can, by definition, only be done by a proper court.

(Omitting all the other problems with mandatory independent settlement schemes for brevity.)

Wenn ich keine Möglichkeit habe, den Text auf Deutsch zu lesen, finde ich es schwierig, etwas so Komplexes wie einen Gesetzestext/eine Richtlinie zu verstehen oder zu kommentieren. Bitte führen Sie eine Sprachauswahl für Ihre Nutzer ein, sonst bleibt Ihre Initiative nur etwas für Leute, die Englisch perfekt beherrschen, also elitär und undemokratisch. Mindestens Deutsch (ca. 100 Mio. Muttersprachler) und Französisch (ca. 70 Mio Muttersprachler) in Europa sollten ebenfalls zur Verfügung stehen

Vielen Dank für den Kommentar und das Interesse – wir arbeiten gerade an der Überetzung der Webseite, die nun unter https://www.greens-efa.eu/mycontentmyrights/de/ zu erreichen ist. Leider haben wir zurzeit keine weiteren Kapazitäten, den Gesetzentwurf selbst zu übersetzen. Wäre es möglich, wenn Sie einen allgemeinen Kommentar mit Ihren Ideen zusammenfassen könnten, die wir dann gerne einarbeiten?

A section on transparency in relation to content moderation that does not deal with illegal content might be useful. A lot of the content reported as being illegal is likely to be removed on the basis of terms of service, so some transparency/good practice might be useful.

ILGA-Europe supports the position of civil society organisations such as EDRi and Access Now that a harmonised, transparent and rights-protective notice-and-action framework should be required to be an integral part of any IT platform. Such a framework will empower users to flag potentially illegal content and set clear, transparent and predictable requirements for intermediaries, and will require providers to put processes in place to deal responsibly and timely with such notifications with due regard for users’ free expression rights.

At the same time, ILGA-Europe believes that the proposed draft legislation should be accompanied with strong action by EU institutions and Member States against any use of hate speech, in especially by public leaders and politicians, including the clear condemnation of such hatred as incitement to discrimination, hostility or violence towards vulnerable groups, including against LGBTI people.

In this regard, ILGA-Europe calls on Member States to:

• Review existing laws against hate speech and hate crimes to ensure that it covers all hate speech, including online and clearly prohibits the incitement to discrimination, hostility and violence based on all grounds, including sexual orientation, gender identity and gender expression and sex characteristics; or develop ‘hate speech’ legislation that meet the requirements of legality, necessity and proportionality, and legitimacy, and subject such rulemaking to robust public participation;

• Actively consider and deploy good governance measures, including those recommended the Rabat Plan of Action , to tackle hate speech with the aim of reducing the perceived need for bans on expression;

• Establish or strengthen independent judicial mechanisms to ensure that individuals may have access to justice and remedies when suffering cognisable harm from hate crime and speech, including in online world.

In addition, to further harmonisation of EU legislation and ensure full protection of vulnerable groups against hate speech both in offline and online worlds, the European Commission should assess EU legislation on how it protects all people from all forms of hate speech. The Commission, working with future EU Presidencies, Member States and the European Parliament, should explore grounds for legislative measures on prohibition of incitement to discrimination, hostility and violence based on all grounds, including SOGIESC.

National and European Union legislation on prohibition of incitement should be based on clear and accurate definitions of the concepts of “incitement”, “discrimination”, “violence” and “hostility”. All definitions should be based on sound and consistent human rights standards. In this regard, legislation can draw, inter alia, from the guidance and definitions provided in the Camden Principles.

We would like to raise three concerns. These three issues have not or not extensively enough.

1. The regulation should exclude public authorities as notifiers. Those public authorities often have the power to take down content that is considered to be illegal already. Of they don’t have that power, that was probably for a good reason. This power comes with all kinds of safeguards. For example, to order the take down of content Dutch police first needs to obtain a warrant from a judge. If they were to be allowed to notify a content hosting provider based on this regulation and content is subsequently taken down, the authority would have an easy way to circumvent safeguards.

2. The regulation should ensure proportionality when content is taken down. What if the content that is manifestly illegal can only be taken down by making unavailable an entire website or even server? Should the provider take down illegal content and by doing so, take down other, legal, information in the process? Or should all information remain accessible, including the illegal content? This can happen when the hosting provider only provides the rack space and network connectivity for server, while not having access to the data stored on the server (“colocation” is the term often used for this kind of service).

3. The regulation should differentiate between the different types of content. The impact of an image of sexual exploitation of children is different from the impact of an infringement of copyright. For example, when receiving of a notification of an image of sexual exploitation of children an immediate take down rather than waiting for a response to the notification of the content provider is probably justified. On the other hand, in the case of an alleged infringement of copyright not much (additional) harm is made when the hosting service provider would wait for a response of the content provider. The same applies to the previous point: the type of content will influence the proportionality.

Furthermore we would like to support the comments made by others, in particular those of Access Now, Electronic Frontier Foundation and Joe McNamee.

true, and should be redundant (or merged with) with e)